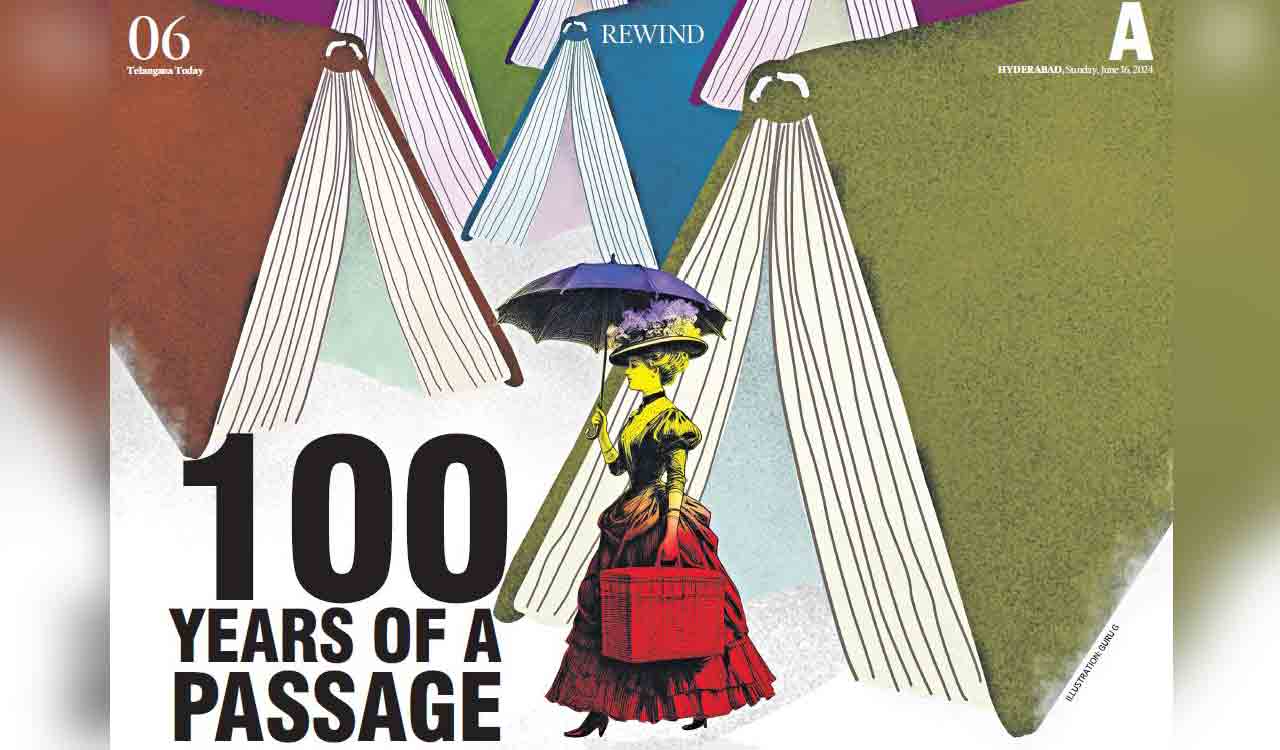

Rewind: 100 Years of a Passage

The iconic novel about the ‘East-West encounter’, A Passage to India, with its exploration of the class-race intersection, gender and humanism, turns 100

– By Pramod K Nayar

A cave, an English girl, an Indian tour guide. All the elements in conjunction for a mystery, a misunderstanding and a mishap. The novel’s opening though seemed the antithesis of a mystery in its account of drabness and monotony:

Also Read

- Except for the Marabar Caves — and they are twenty miles off — the city of Chandrapore presents nothing extraordinary. Edged rather than washed by the river Ganges, it trails for a couple of miles along the bank, scarcely distinguishable from the rubbish it deposits so freely. There are no bathing-steps on the river front, as the Ganges happens not to be holy here; indeed there is no river front, and bazaars shut out the wide and shifting panorama of the stream. The streets are mean, the temples ineffective, and though a few fine houses exist they are hidden away in gardens or down alleys whose filth deters all but the invited guest. Chandrapore was never large or beautiful, but two hundred years ago it lay on the road between Upper India, then imperial, and the sea, and the fine houses date from that period. The zest for decoration stopped in the eighteenth century, nor was it ever democratic. There is no painting and scarcely any carving in the bazaars. The very wood seems made of mud, the inhabitants of mud moving. So abased, so monotonous is everything that meets the eye, that when the Ganges comes down it might be expected to wash the excrescence back into the soil. Houses do fall, people are drowned and left rotting, but the general outline of the town persists, swelling here, shrinking there, like some low but indestructible form of life.

This paragraph opens one of the more complicated novels about the British Empire, the iconic A Passage to India, whose 100th anniversary falls this year.

Edward Morgan Forster (1879-1970), in equal parts puzzled and critical of India, angry at the Empire and those who ran it, was attempting to understand the ‘real India’, just like his character in the novel, Adela Quested. Passage is his most famous work.

Forster’s interest in thinking through the relationship between the East (embodied in India) and the West (Britain), especially in the context of cultural encounters set within the framework of colonial rule, produced Passage which appears to raise more questions than answers. It presents the land as an unfathomable mystery, finds the British in India uniformly obnoxious, and offers a humanist vision of connections, a vision permeated by a sadness that such connections cannot move past the barrier of racialised imperial relationships.

Passage was also a lavishly produced Merchant Ivory film starring Victor Banerjee as Aziz, Judy Davis as Adela and Peggy Ashcroft as Mrs Moore.

Strange Land

Forster’s novel cast India as a space of mystery. The Marabar Caves in which the alleged assault of the English girl (Adela) by the Indian man (Dr Aziz) occurs is an embodiment of this mystery. There are, as a result, works on Forster that focus almost entirely on the Caves (‘what really happened in the Marabar Caves?’) Here Forster undoubtedly stereotypes India as a place of chaos, superstitions, and of course, mud.

Forster’s brilliance lies in the emphasis he lays on how British imperial governance addresses this strange land, reorganises it, interprets it. One of the most vocal critics of the Empire in the novel is Mrs Moore, who is also one of the few to recognise the ineffable mystery that is the subcontinent. She makes an astonishing pronouncement about the land when she sees a wasp inside her home:

- Perhaps he mistook the peg for a branch — no Indian animal has any sense of an interior. …insects will as soon nest inside a house as out; it is to them a normal growth of the eternal jungle

It is open to question whether Mrs Moore is depicting India as a land that is accepting of every form of life, even when this life intrudes into specifically human spaces. Decades later, this same sense of space that refuses to abide by borders, will be echoed in AK Ramanujan’s poem, ‘Small-scale Reflections on a Great House’, a poem that is also a manifesto for an inclusive, tolerant, plural India:

- Sometimes I think that nothing that ever comes into this house goes out.

This is a land that the British have carved up, with polo grounds and tennis courts and what not. Some of these efforts, like polo, were attempts to bring together the ruling whites and the local elites as a way of mitigating the racial binary, as the historian David Cannadine has argued. Elsewhere in the novel, the Bridge Party is a space of the encounter of classes and races, but on terms determined by the British. When the natives actually do turn up, the British are surprised: “Oh, those Purdah women! I never thought any would come. Oh dear!’ says Mrs Turton. The court scene where Aziz is being prosecuted is also a space over which the British have absolute control.

The Marabar Caves are the epicentre of the ‘muddle’ as Mrs Moore calls it. The Caves are symbolic of the emptiness, which is paradoxically full, at the heart of existence and meaning. They represent the transcendence of time, space, people and differences. The one who comes closest to capturing this transcendence is the symbolically named ‘Godbole’, the learned Brahmin, who suggests that Adela may have hallucinated inside the Caves, implying that India is not so easily understood or formulated in a phrase. The message of the Caves, as Forster attempts it, is a philosophical one: ‘everything exists, nothing has value’. The Caves are also what the critic Nalini Natarajan has called ‘entropic spaces’: they are a frontier across which the English, and the women in particular, are ‘devoured’ (Natarajan). Then finally there are the open spaces at the end of the novel where Fielding, the Englishman with the most empathy for Indians after Mrs Moore in the novel and who befriends Aziz, and Aziz go riding decades later.

Strangers in the Land

During the course of the novel, Forster pinpoints not just Britain’s racial imaginary and practices but also the class dynamics that structure British society in Chandrapore. The people who run the Empire are not just strangers to the land: they are determined to stay that way, distanced from the people they rule, arrogant and insular.

Fielding, the British in the town decide, was not really a ‘pukka sahib’ due to his class origins:

- The gulf between himself and his countrymen … widened distressingly … The feeling grew that Mr. Fielding was a disruptive force…

Fielding discovers that race and class go together in British India:

- He had discovered that it is possible to keep in with Indians and Englishmen, but that he who would also keep in with Englishwomen must drop the Indians. The two wouldn’t combine. Useless to blame either party, useless to blame them for blaming one another.

Ronny Heaslop, representative of the insular British officialdom that ran the Empire, is described as a man who knew only one kind of relationship with Indians:

- The only link he could be conscious of with an Indian was the official…As private individuals he forgot them.

His arrogance riles Mrs Moore who accuses him and his colleagues of posing like gods in India, to which Heaslop retorts: ‘Indians like gods’.

The relationship between Fielding and Aziz, with overtones of the homoerotic, is the pivot in Forster’s dissection of race relations. When the novel ends, Aziz, who has seen the worst of the British Empire in his persecution, and Fielding attempt to keep their friendship alive.

Forster layers class with gender and gender with race. Heaslop despises all Indians, and he wishes to gain dominance over them. Fielding despises most British. Adela is not yet sure where she stands on the colour-line. Aziz, hovering between the servile and proud native types, gains Fielding’s trust but is also disappointed in him. He is upset when his mention of the post-impressionist art is dismissed by Fielding with ‘Post Impressionism, indeed!’ Forster writes of the moment:

- Aziz was offended. The remark suggested that he, an obscure Indian, had no right to have heard of Post Impressionism — a privilege reserved for the Ruling Race.

Aziz, the lawyer Amritrao, and the clearly detached Godbole represent moments of resistance in the race-class dynamics. Aziz is proud of his Islamic culture and Persian roots. In the court scene, Amritrao objects to the spatial and seating arrangements:

- We object to the presence of so many European ladies and gentlemen up on the platform… they will have the effect of intimidating our witnesses. Their place is with the rest of the public in the body of the hall.

The English women are unfailingly class-conscious and racist. Forster like the historian Percival Spear believed that the British Empire paid the price for the arrogance of its Englishwomen. Mrs Turton in the novel is a prototype of such a woman. She advises Adela: ‘you are superior to everyone in India except one or two of the ranis, and they are on equality’. The critic Leela Gandhi has noted how colonial discourse posited a ‘native man versus white woman’ battle. Forster presents Adela as manipulated by her desires (in the court scene, in a telling Forsterian moment, Adela’s attention is transfixed on the half-naked, sweaty body of the punkah-boy). Forster makes Adela an unwitting player in the erotic politics of race when she, at the behest of the other English, accuses Aziz of molesting her. During the trial she exonerates Aziz, which results in her being excommunicated by her fellow English.

Bridging Humans

Critics like Eric Wasserman have proposed that Passage is an attempt to think through the ideal of totality. This totality may be found only within Hindu philosophy, embodied in the character of Godbole. For critics like James McConkey, Godbole is Forster’s voice in the novel, embodying the philosophy of detachment from the world, a downgrading of individual consciousness in favour of a cosmic one, and above all, an awareness of unity. When Godbole includes the universe in his spiritual life, argues the critic Hugh Maclean, he encompasses everything. This is the ability to place the self within a transcendental frame — which, for Forster, is something the West has been incapable of. Connections across humans and the universe require us to transcend ourselves. But there are lower level connections too.

When the novel opens, Hamidullah and Aziz wonder whether the Indians can really be friends with the British. They conclude that it is impossible so long as the Empire holds sway and determines social relations.

‘Only connect’, the epigraph to Passage, was Forster’s motto throughout his career. He defined it in Howards End:

- Only connect! … Only connect the prose and the passion, and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its height. Live in fragments no longer.

But to ‘only connect’ without the politics and the governments, and in the absence of any understanding of India is the challenge. Forster anticipating the dictum, the ‘personal is the political’, implies that the personal is not possible outside of the political.

Forster’s humanist vision intertwines with a hard-headed pragmatism. This is finally what leads him to write as the remarkable final paragraph. Aziz and Fielding are riding, there is the expectation of the horses and their riders continuing, close, on the same path, but the uneven fractured terrain does not allow it:

- But the horses didn’t want it — they swerved apart; the earth didn’t want it, sending up rocks through which riders must pass single file; the temples, the tank, the jail, the palace, the birds, the carrion, the Guest House, that came into view as they issued from the gap and saw Mau beneath: they didn’t want it, they said in their hundred voices, “No, not yet,” and the sky said, “No, not there.”

On the earth itself, the colour line is etched. It divided the land, it divides humanity.

(The author is Senior Professor of English and UNESCO Chair in Vulnerability Studies at the University of Hyderabad. He is also a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and The English Association, UK)

Related News

-

Cartoon Today on December 25, 2024

1 hour ago -

Sandhya Theatre stampede case: Allu Arjun questioned for 3 hours by Chikkadpallly police

2 hours ago -

Telangana: TRSMA pitches for 15% school fee hike and Right to Fee Collection Act

2 hours ago -

Former Home Secretary Ajay Kumar Bhalla appointed Manipur Governor, Kerala Governor shifted to Bihar

2 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Organs of 74-year-old man donated as part of Jeevandan

2 hours ago -

Opinion: The China factor in India-Nepal relations

3 hours ago -

Editorial: Modi’s Kuwait outreach

3 hours ago -

Telangana HC suspends orders against KCR and Harish Rao

4 hours ago